Oil on canvas

54.6 x 45.1 cm. (21 1/2 x 17 3/4 in.)

frame: 82.2 x 73.0 x 7 cm. (32 3/8 x 28 3/4 in.)

L.1988.62.14

Lower right: Manet

The artist’s estate sale, Hôtel Drouot, 5 Feb. 1884, no. 36, sold to M. Samson, possibly a pseudonym and/or agent. Auguste Pellerin (1853–1929), Paris, by 1902; [sold to Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Paul Cassirer and Galerie Durand-Ruel, 2 Feb. 1911]; sold to John Quinn (1870–1924), New York, 3 Apr. 1911; [sold to Durand-Ruel, New York, 9 Nov. 1911]; sold to Martin A. Ryerson (1856–1932), Chicago, 24 Apr. 1912; by descent to Mrs. Martin Ryerson, Chicago; her bequest to The Art Institute of Chicago, 29 May 1937; [sold to E. & A. Silberman Galleries, New York, 29 Apr. 1947]; sold to Henry Pearlman, New York, by May 1953; Henry and Rose Pearlman Foundation, after 1974.

Manet came from a well-to-do bourgeois home and so found an ease and familiarity in depicting women of his class. He chose to paint this young woman in profile, and to hide her eyes behind a dark smudge of black veil, making it difficult to read her expression. She wears what appears to be a wealthy woman’s walking ensemble, one designed for promenading on the then recently constructed boulevards and in the newly built parks of Paris.

Never exhibited during Manet’s lifetime, this painting has provoked speculation about whether the subject was a friend or a model. She is dressed in a walking suit, and the object she carries is identified as a parasol, umbrella, or walking stick. The picture epitomizes what the poet and critic Charles Baudelaire considered a defining feature of images of modern life: the changing fashions of ladies’ dresses.

The painting dates to the late 1870s, when Manet was experimenting with the high-keyed colors and feathery brushstrokes of younger artists such as his friend Claude Monet and his sister-in-law Berthe Morisot. They urged Manet to take part with them in the independent exhibitions organized by Edgar Degas and other Impressionists but Manet – who longed for official recognition – refused, continuing to submit works to the jury of the Salon, the annual art exhibition sponsored by the French government.

There was one occasion in all my years of collecting, when I was rather lukewarm about a painting. It was a work by Manet that had been originally quoted at $4,000, and then,…

There was one occasion in all my years of collecting, when I was rather lukewarm about a painting. It was a work by Manet that had been originally quoted at $4,000, and then, toward the end of the season, at $35,000. One day, the dealer buttonholed me on 57th Street and insisted that I come up to his gallery. He wanted to sell me the painting, and he did—for about half the original price. I’ve been thankful to him ever since. However, a sad aftermath to this transaction occurred a short time later. This same dealer had a small gem of a painting, a Cézanne still-life, that he offered me for about $25,000. I should have bought it, but I was planning to leave for Europe a few days later, and not having enough time, nor being in the mood to go through a tug of war with this dealer over the right price, I passed up an opportunity that I regret to this day. Of course, few dealers are like that, otherwise collecting would not be the fun it is.

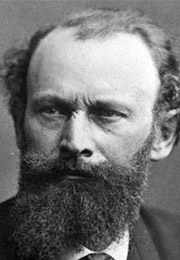

Édouard Manet (1832-1883)

Widely hailed as a pivotal figure in modern art, Édouard Manet (1832–1883) presented a new vision of modern Parisian life in his paintings, paving the way for many of the developments of Impressionism. Manet’s paintings focused on life in the city that was undergoing dramatic physical and social transformations during the eras of the Second Empire and the Third Republic. At the same time, he offered a radical new formal approach to painting, eliminating traditional notions of academic modeling and bringing attention to the materiality of paint itself.

Manet came from an upper-class family; his wealth freed him from the necessity of earning a living and allowed him to pursue an artistic career. He studied with Thomas Couture from 1850 to 1856, but he would soon abandon many of the academic precepts he learned in Couture’s studio. Manet’s paintings, although mostly contemporary in subject, integrate references, in terms of technique and composition, to the Old Masters whom he closely studied at museums across Europe, including Flemish, Dutch, Spanish, and Italian schools of painting. The collision of the modern with Old Master references was highlighted in controversial paintings such as Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863), which placed bourgeois libertines in the role of river gods, derived from a composition by Raphael, and Olympia (1863), which cast a modern courtesan in the role of Titian’s Venus of Urbino.

Although he never exhibited with the group, Manet was a friend to many of the Impressionists, including Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Those artists were in no small part influenced by Manet’s focus on depicting modern life, and he was in turn encouraged by his association with them to experiment with a brighter palette and looser handling of paint. Portraits were among his central subjects, and he deftly captured the social cues apparent through the fashion and deportment of each individual, as in Young Woman in a Round Hat. In his astute attention to the particular character of his time, Manet has been seen as an exemplar of Baudelaire’s idea of the “heroism of modern life.”