Oil on canvas

27.0 x 17.1 cm. (10 5/8 x 6 3/4 in.)

frame: 42.5 x 31.5 x 5 cm. (16 3/4 x 12 3/8 x 1 15/16 in.)

L.1988.62.1

Louis Bernard, Paris; [sold to Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, 28 Sept. 1910]; sold to Jos Hessel (1859–1942), Paris, 11 Nov. 1910. [Galerie Bignou, Paris, after 1929]. [possibly Alexander Reid & Lefevre, Ltd., London, by June 1939]. [Bignou Gallery, New York, by October 1940]. [Dalzell Hatfield, Los Angeles]. [Fine Arts Associates, New York, by 1955]; sold to Henry Pearlman’s daughter Marjorie Scheuer, New York, by 23 Sept. 1955, possibly acting on behalf of her father; Henry Pearlman, by 1959; Henry and Rose Pearlman Foundation, 1981.

Conservator’s Note

The artist first used a black crayon-like instrument, perhaps a lithographic crayon, to sketch in a clear outline of the figure; he then applied thinned oils within the border defined by the black outline.

Cézanne made more than two hundred paintings, drawings, lithographs, and watercolors of bathing figures. This is a study, cut from a larger canvas that probably contained other studies, and it appears to have supplied the pose for a figure in a painting now in Detroit. Cézanne’s childhood friend, the author Émile Zola, described two young people swimming in a river in his novel La Fortune des Rougon (1871), an episode that seems based on memories of the boys’ swimming expeditions. Joachim Gasquet, who became Cézanne’s confidant in 1895, described the bathing parties as “their supreme joy,” lasting from morning to evening, so that the youths were saturated with the landscape and “the countryside became part of them.”

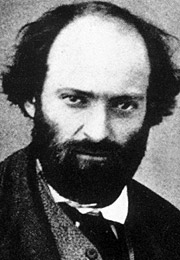

Paul Cézanne (1839-1906)

Cézanne is recognized as one of the great innovators of late 19th- and early 20th-century art, whose work has influenced countless modern artists. With an introverted temperament and generally anti-establishment stance, Cézanne forged a new approach to painting that sought not only to reflect nature but also to express his own response to it. Although during his formative years he exhibited with the Impressionists, he ultimately felt at odds with their emphasis on fleeting experience, seeking greater solidity through painterly form and structure.

Born in Aix-en-Provence, Cézanne studied drawing early on, but, fulfilling his father’s wishes, he later enrolled in university to study law. In 1861, however, he left for Paris, where he studied at the Académie Suisse and copied Romantic and Baroque art at the Louvre. Failing to gain entrance to the École des Beaux-Arts, and constantly rejected by the official Salon, Cézanne rebelliously painted in an intense, even violent, manner, with thickly encrusted paint. Finding a mentor in the Impressionist painter Camille Pissarro, in the 1870s Cézanne lightened his palette and started working directly from the landscape. He was influenced by the solidity of Pissarro’s brushwork and compositional structure, yet, like Paul Gauguin, whom he met in 1880, he sought to express his own personal perceptions and sensations through his views of nature.

By the late 1870s, Cézanne’s paintings showed increasing emphasis on mass and structure, and he developed a system of parallel brushstrokes, known as his “constructive stroke,” that conveyed the volume of both form and space. With mind and eye working in concert, Cézanne built up his pictures slowly and deliberately, often while directly confronting his motif, whether a landscape, still-life, or portrait. In Aix, the prominent form of Mont Sainte-Victoire became one of his dominant motifs from the mid-1880s until the end of his life. Attracted to its enduring geometric form and the changing views offered by different light and angles, Cézanne created more than thirty paintings in oil and watercolor that conveyed his intense examination of the subject’s underlying structures as well as the shifting nature of perception.

Cézanne used the medium of watercolor to experiment with form and structure, creating a wide range of effects through transparent planes of color and strokes of pencil. The exceptional luminosity of watercolor allowed him to play with light as a constructive element, while often using blank passages of paper to heighten the sense of space and form. Cézanne’s watercolors thus had a great influence on his oil paintings, seen particularly in his use of exposed areas of blank canvas as a constitutive element and passages that reveal open compositional structures, as exemplified in Route to Le Tholonet. Many successive generations of artists, from the Cubists and Fauvists to Abstract Expressionists, would be influenced by Cézanne’s experimental legacy.