Oil on canvas

101.6 x 76.2 cm. (40 x 30 in.)

frame: 128.5 x 103.5 x 7 cm. (50 9/16 x 40 3/4 x 2 3/4 in.)

L.1988.62.30

Signed lower right: OK

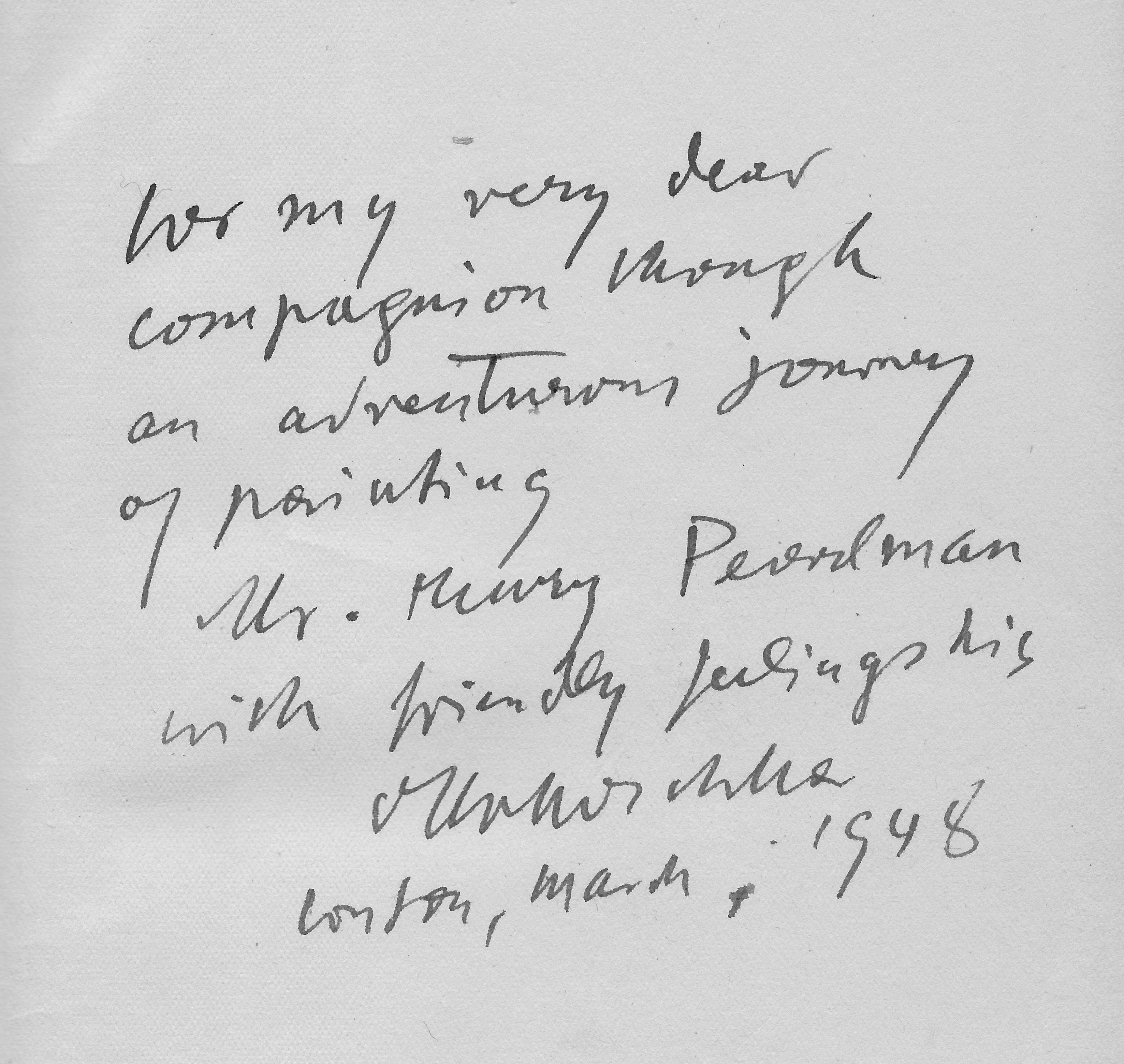

Commissioned from the artist by Henry Pearlman in Mar. 1948; Henry and Rose Pearlman Foundation, by 1959.

Kokoschka painted Pearlman’s portrait in London. The artist’s wife, Olda, recorded in her journal the sittings that took place daily from March 15 through March 22, and from April 5 through April 7, 1948. Kokoschka conversed with his sitters, and Pearlman must have spoken about his house on the Hudson River as well as his daughters, for Marge and Dorothy Pearlman appear as young girls in the background, catching fish. The flash of Pearlman’s bright eyes and the nervous drawing that describes his body and hands bring the portrait to life. Kokoschka did not always get along with his sitters, but he became such a good friend of Pearlman that he stayed with the Pearlman family for a month on his first trip to the United States, in 1949.1

I have had the good fortune to have my own portrait done by two great artists: a painting by Oskar Kokoschka, and a sculpted head by Jacques Lipchitz. Both were exhilarating…

I have had the good fortune to have my own portrait done by two great artists: a painting by Oskar Kokoschka, and a sculpted head by Jacques Lipchitz. Both were exhilarating experiences. My sittings for the bust with Lipchitz totaled twenty-nine; they were at my office, and while sitting on a revolving stool, with my painting collection all about the room, and few distractions. If I had received nothing else for the money I had paid the artist, the experience would have been worth it.

I arranged to have Kokoschka do my portrait when I met him in London in 1948. We had fourteen sittings of about two hours each, and I went to each sitting relishing the time we would spend in conversation; in fact, it was one of the highlights of my life. He was a man of the world, with a great interest in public affairs, but he also put a good deal of himself into the painting, and appeared to be exhausted after each sitting. I invited him to come to the United States and live with us, which he did the following year.

In 1949 Kokoschka came to New York and spent a month at my home. The day before he arrived, I bought a painting of his at Parke Bernet, wanting to surprise my friend Oskar. After he was settled for a day or two, I put the painting on the mantelpiece, and asked him how he liked it. He studied it for a few minutes and said, “Henry, this is a bogus.” Somebody had copied one half of one of his paintings on one side, and one half of another painting on the other. I brought it back to Parke Bernet, and explained what Kokoschka had said. They checked and found that they had nor yet paid the consignor, and gave me my money back.

During Kokoschka’s stay with us, I was offered a watercolor of his by a very reputable gallery. I showed it to him, and he was quire puzzled by it. He said the drawing was correct, except that somebody had made a watercolor out of the drawing. I sent it back to the dealer, who was quite dismayed, as he had purchased it in good faith.

Kokoschka was installed on the fifth floor of our home, which was a glass solarium that I used for hanging paintings. Oskar’s room was at the end of the gallery, and whenever he walked up to the fifth floor he would see two Soutine landscapes before he entered his room. After a few days he asked me if I would move the Soutines. He didn’t think too much of Soutine as a painter. I told Oskar that they were my choice paintings at that time, and I’d like him to live with them a little longer.

Several weeks later, he was in my office, where a third Soutine landscape was hanging, and I noticed he was quite taken with it. He must have stood in front of that painting some twenty minutes. A friend of mine came in during that time. Kokoschka came over and shook hands with my friend, and then went back to the landscape. When the friend had left, Oskar came over to me and said, “Henry, Soutine is a painter.” I suspected that Oskar found something in the landscape where Soutine had solved a problem that he had been unable to solve in one of his own paintings. He never said another word about the two Soutines that hung in my home.

Kokoschka later invited me to join him on a trip to Vienna, where he had been commissioned by the Burgermeister of Vienna to do his portrait, which would take about ten days. He stayed with his brother, and I stayed at a hotel. Kokoschka was given a dilapidated automobile by the city for use during his stay, which had an official emblem on it; he and I would travel through the streets of Vienna, and every time the car stopped at an intersection, a traffic policeman would salute the emblem. Oskar would turn to me and say, “Henry, everybody knows I’m in town!”

I would meet Oskar every couple of days, and he would describe the sittings with the Burgermeister. After the first few days he told me what a wonderful, kindly man his sitter was. On the third and fourth trips he described him as a very shrewd politician, and after the sixth or seventh sitting, described him as being sly as a fox. When the portrait was done and ready to be unveiled, a small admission was charged to benefit a local charity. There was a large crowd for the event, and when they removed the sheet covering the canvas, there was an excellent likeness of the Burgermeister, but one of his teeth was sticking out the side of his mouth. Of course, Kokoschka was a dangerous man to have your portrait done by, a physiological painter, and you never knew for sure how the portrait would come out.

Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980)

Kokoschka was a painter, printmaker, and writer who forged an expressive style that sought to convey emotion and humanistic ideals. Born in a small town in Lower Austria, he was raised under difficult economic circumstances—yet was able to move to Vienna, where he trained at the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Arts and Crafts) between 1904 and 1909. Kokoschka admired the work of Gustav Klimt and other members of the avant-garde Vienna Secession movement. Many of Kokoschka’s early works, which stressed heightened emotionality, proved controversial, and when he exhibited them in 1908 and 1909 critics derided them as the work of a madman. Through his supporter, the influential architect Adolph Loos, he became friends with members of Viennese intellectual circles, many of whose portraits he painted. His early portraits in particular demonstrate how he strove to convey the psychological and spiritual aspects of his sitters. He also created drawings early in his career for the journal Der Sturm; these illustrations wereadmired by German Expressionists

In the wake of a tumultuous affair with Alma Mahler (widow of Gustav Mahler and a composer herself), which effected much of his work, Kokoschka volunteered for military service at the outbreak of World War I and suffered serious wounds while serving on the Eastern Front. In 1916 he moved to Dresden; three years later he became professor of the art academy. His work shifted from a focus on angst-ridden figures to a more colorful palette, and townscapes became his major subject. Kokoschka left Dresden in 1923 to travel across Europe, North Africa, and the Near East. He painted panoramic pictures of cities depicted from elevated viewpoints, with vibrant colors and lively brushwork. After fighting in Vienna gave rise to an authoritarian regime, Kokoschka settled in Prague in 1935 and became a Czechoslovak citizen. His work was seized by the Nazis and displayed in their infamous Degenerate Art exhibition. When the Nazis invaded, Kokoschka took refuge in London, becoming a British citizen in 1947. Dedicated to Republicanism and humanist values, he created works that responded to the crisis of the Second World War. During the last several decades of his life, he traveled extensively in Europe and the United States, continuing to paint landscapes, portraits, and mythical and allegorical scenes. From 1953 to 1963, Kokoschka ran a summer academy in Salzburg, attracting young artists from around the world. He reclaimed his Austrian citizenship toward the end of his life.